* SPOILER NOTE: I’ll restrict any specifics to after the jump, so that scroll-by readers who haven’t seen the finale aren’t accidentally tipped off.

We started recapping The Good Wife here in season six. Late in the game, yes, but at first it was simply a show we loved to watch. Then it was a show whose business-casual clothes we devoured. Then it sagged, and it was the fifth season’s rebound that pushed us optimistically into covering it here; we thought it would be fun to discuss and fun to ogle. For a time, it was. But in season seven we slowly stopped, exhausted when the well felt poisoned again. And last night, it officially ran dry — somehow both prematurely and not a moment too soon.

It had long seemed inevitable that Robert and Michelle King would want to close on some kind of parallel to the pilot, in which Alicia stands by her man in public and then slaps him behind the scenes before pulling herself together and pressing on into the breach. But in cleaving to that goal, it hindered both the series’ growth and Alicia’s. It kept her tethered to Peter long past their expiration date. It kept her, and her future, under a man’s thumb — no matter how often she tried to assert her independence in other ways. Alicia was always The Good Wife even when she wasn’t, because she was never permitted to be anything else. Her broken marriage loomed over everything, forced her down foxholes, and poisoned as much of her life as profited from it.

Here’s how it played out: In the pilot, we open on Alicia and Peter’s clasped hands as they walk out to face his press conference. She grapples with nerves and agitation, and once off-stage, she slaps him — a satisfying strike even though we’ve only just met the Florricks. Last night, it repeated itself, this time for Peter to accept a plea deal on one corruption charge and resign as Governor. It’s the sight of a silhouette she believes to be Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s Jason that gets Alicia fidgety; instead of leaving the dais as a team, she lets Peter fumble for air as she dashes off to chase Jason, and of course he isn’t there. Then she turns and an enraged Diane, betrayed that Alicia allowed Lucca to rip apart her husband Kurt (Gary Cole) on the stand, desecrating her marriage with implications of infidelity (we never hear how Kurt answered that question, and nor does Diane, who simply got up and left) and shredding his reputation in the process. This time, Alicia takes the slap, from her former mentor and idol. As she wipes away the tears and pulls herself together, it’s Alicia’s cheek that’s stinging, not Peter’s. And that’s how we leave it.

You could chalk that up to audacious storytelling and ambiguity. Certainly there’s boldness in opting not to tie up your show in a nifty, potentially trite little bow. But when The Sopranos famously cut to black at the end of its show, it was like eating a pretty satisfying meal and then finding out they weren’t serving dessert. It didn’t ruin what came before it, but yeah, maybe you wished for that one final hit of sugar to button up the night. The Good Wife’s decision felt emptier, borne of a desire for a nifty parallel rather than a triumphant, carefully plotted arc. It was all show and no substance.

Indeed, the finale and the weeks preceding it showcased so much of what’s been frustrating and at times alienating about the show’s limp toward oblivion. The plot, rather than a character, got behind the wheel and drove us home; a dredged-up court case from long ago — which no one remembers, prosecuted by a character that just showed up a couple weeks ago — hijacked the whole affair. I love Cush Jumbo, but she shouldn’t have had more screen time than Cary Agos, a beloved regular who received perfunctory epilogue (he’s a teacher, he seems happy). Diane Lockhart, one of the grooviest and most self-assured characters on TV, was stuck with potential cracks in her marriage and in her firm. She felt… relegated, somehow. Knocked down a tier. And for what? So that the parallel ending could happen. Grace deferring Berkeley to stand by her man — her father — was an interesting alarm bell for Alicia, because it represents the shadow Peter has cast over all their lives. But Zach quitting Georgetown at 19, so he could move to Paris with a 23-year old fiance who accepted him because marriage is a tax-friendly, impermanent adventure, was merely an excuse for Alicia to treat her son once more with scorn. The Good Wife was at its worst when it viewed the characters with contempt, and Alicia’s children suffered the most from that.

At times, though, The Good Wife also treated its audience with contempt. (Although this, at the end of our recap, made me laugh, it’s also pretty telling.) And that’s an even bigger problem. The tightrope showrunners have to walk is a tenuous one, because we live in an age where fandom blurs the lines and attachment breeds ownership. Viewers want this pair, and that, or complain about lost plots and dropped characters, often without any insight into the extenuating circumstances. Maybe a certain actor was not readily available, or the budget changed. (Maybe the actors’ personal lives make professionalism impossible, or at least unavailable.) The Good Wife dips into Broadway’s well of talent with wonderful frequency, but the flip side is, when comfortingly familiar recurring face Geneva Pine gets the role of a lifetime in Hamilton, she necessarily disappears from the canvas. What we see on the screen is only ever a fraction of the story, and while it’s completely valid to complain, it can’t be without sympathy or curiosity. When Josh Charles decides to leave, and you don’t want to spend your time begging him to come back for a short arc, why not just kill him and let the pieces fall in new places? That’s playing the hand you’re dealt, and The Good Wife handled it well. His death had meaning, import, and impact.

But if you stand back and look at The Good Wife, a show once so marvelous about its rotating stable of recurring judges and attorneys, you see a past littered with characters it simply assumed you were too dumb to remember. Like Taye Diggs, or investigator Robin Burdine (Jess Weixler). Carey Zepps vanished; his seeming replacement did too. The female attorney they hired this season? I don’t even remember her name. Michael Boatman, a former partner… does anyone even know when he left? It’s hard to trust a show that feels as if it’s being written by new hires who didn’t bother to binge it before they joined, and in that case one looks to the creators, the founding showrunners, to impose a sense of emotional continuity. They did not provide it. Instead, lawyers bedhopped with astonishing regularity. The firm names changed so often that I don’t even remember what half of them were. Plots came and went, and every move started to feel like nothing more than the need to do something. People stopped being characters and simply became chess pieces. They even engaged in some tedious plot gymnastics just to get Alicia and Diane’s startup firm back in the original offices, something that became a clear microcosm of a larger problem: What, then, was even the point?

Nowhere is that more debatable than in Alicia’s ending, or lack thereof. Her self-actualization is the journey we signed up to take. The finale suggests she never got there; that she’s still looking for something she doesn’t know how to find. And that of course is reflective of reality. We don’t always get there. But neither is The Good Wife hard-boiled realism. This is not the show we came to for hard truths and bleak emotional byproducts. We wanted to see our girl WIN. Now, showrunners cannot and should not chain themselves to what fans demand. Viewers, however much we might wish it, are not the writers. Nor should we be. TV writing rooms have to find ways to tantalize, appease, and jolt the viewership without stranding themselves on an island with no lifeboats, and that’s going to involve asking fans to take leaps with them that we might not like at first. Take Nashville, which has had to rip apart Juliette and Avery, and yet managed to do it in a way where you fully understand both sides of that story. TV has always been my preferred medium to films, largely because I have so much respect for how hard it is to create 22 hours of story year after year after year, as opposed to two and a half hours of splashier narrative that doesn’t have to worry about long-term contracts.

The Kings themselves have griped about those handcuffs. “It’s just too demanding,” they whimpered recently of a full season of episodes, and yes, it is difficult. But Grey’s Anatomy is rolling deep into double-digit seasons without any such public bellyaching. Michelle King told Variety they created the show because they needed a job. What a gift this longevity should have been. What a Champagne problem. How torturously golden your handcuffs are. For years, we ate up their work, and The Kings too often seem contemptuous of the loyalties that bred. Nowhere was that more evident in the handling of Kalinda and her curious exit, when they teased viewers with a reunion of two actors who refused to share a scene, then merely faked it with awkward splicing and mocked people for being offended. Robert King even condescendingly pointed out that people are silly for believing what they see on TV, because after all, the death of Will Gardner was not also the death of Josh Charles — one of the most obnoxious showrunner statements in recent memory. This was their inability to manage his actors and his set, and impose professionalism where clearly there was none. And their choice to try and dupe viewers. And their choice to tell us we were stupid for caring so much.

That’s why it’s difficult for me to see the finale as satisfying. A good series-ender, I think, buttons the emotional journey. It can start a new one, sure, but it should have a sense of change rather than a sense of stale statis. It should honor the creators’ and writers’ needs while giving viewers a few carrots. Sacrificing the happiness of Diane, one of the few figures left we truly loved,undercuts that.

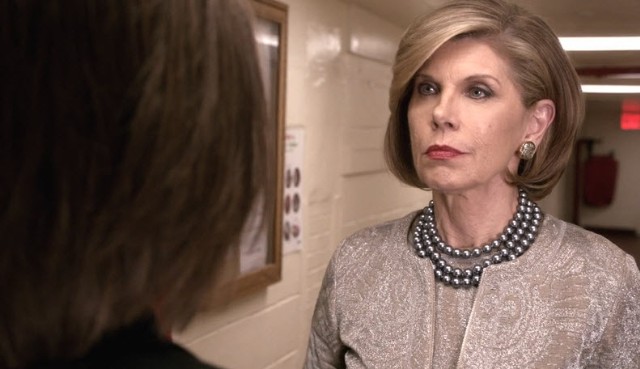

I admit to being satisfied with the slap, mostly because Christine Baranski looked Alicia with such flinty disgust and derision, like she was a spoiled brat, rather than any actual hurt. (It’s my belief that Diane Lockhart is either bulletproof, or simply would never admit to Alicia Florrick that Alicia had the power to hurt her.) And all credit to Julianna Margulies, for being devastated and upset and even crying, before seeming to admit she deserved it, and then pulling herself together. It was an acting tour de force. But I watched it not with admiration, so much as a sense that something I once loved was going to leave me a bit too close to where we started. wasn’t a delicious story morsel for us to swallow.

Because, as much as we’ve rooted for her to make out with her cadre of good-looking co-stars, what I really wanted was for her to claim it all on her own terms. We waited for Alicia to see Peter as the brick he was and cut ties. Imagine the freedom she might have found if she’d left him sooner. Imagine the stories the show could have mined from breaking its mold rather than simmering weakly until the home stretch. Instead, she left him, but didn’t. She was free to indulge her passions, but not really. Not publicly. She still participated in the absurd little play that was their public face, ostensibly for their family, but also because it kept her from having to be alone or from having to step out there before she was ready. She resented its prison, yet reveled in its benefits — the name, the financial clout — until she had a person to walk away for. And while she waited, she became unlikable. Her unrest became bitter. She blamed other people for the decisions that trapped her. These are all human qualities that have their place on TV, but we don’t want to leave our protagonist still victimized by them. Rater, Alicia, the way Julianna Margulies played her, acted like she ran out of gas.

Worse, she was still governed by the men in her life. Her desire to save Peter led her to stomp on Diane. It wasn’t until she had Jason in her bed that Alicia called a time of death on her marriage. Then she went to Jason, only to have him first defer to her needs vis a vis Peter, and then hem and haw about whether he could really be pinned down in Chicago. She decided to choose him anyway… only to have him not return her calls, and her chase his ghost down a hallway before we cut to black. To cap it off, she also spent time with an actual ghost, as Will Gardner returned to mansplain her life to her. She still somehow needed Will to tell her what to do, and give her the freedom to go.

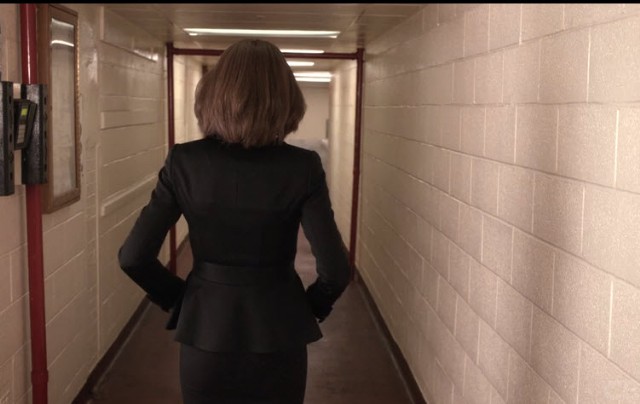

So after 156 episodes, Alicia Florrick was still being steered by other people. Even running for office in season six was something she was goaded into doing, something she resented as she was doing it, and something that was ripped away from her because of Peter. The early promise of the romance with Jason was that Alicia at last started calling some shots, and answering to her own needs; the finale flipped that back disconcertingly and left her again in a hallway, wiping tears from her eyes before straightening her suit. I didn’t need to know what awaited her at the end of that walk. I just wanted to trust that she would be okay when she got there — that Alicia Florrick, in finally escaping the foxhole of being the good wife, would reach the top of a mountain. Instead, I wondered, both of this hour and of the last seven years, “Is that all there is?” Did we, too, overstay in a bad marriage? Perhaps if we had left sooner… and many of you did. The rest of us are in that hallway too, shaken and slapped and stinging. We once sympathized with Alicia Florrick, and now we are her.

And yet they closed on a shot of Wig looking… if not its worst, then close. How fitting that Wig should get the final symbolic word.